Our primary martial arts curriculum is based on the surviving works of Fiore dei Liberi, a master at arms from Friuli in what is now Northern Italy. Fiore was a condottiere (mercenary soldier) during the mid to late 14th century. Later in life, he taught his techniques and strategies, and wrote treatises describing his system.

Fiore gave no formal name to his martial art, simply calling it l’arte dell’armizare (the art of arms). Today it is most often called Armizare. We know that the style outlived him and continued to be taught, because of the surviving manuscript of another master at arms who flourished two to three generations later, Filippo Vadi. Between them, these two men have left us documentation of a complete martial art of a richness and complexity to stand beside any other in the world.

Fiore’s Manuscripts

Click on the thumbnails to see some selected pages from il Fior di Battaglia.

Fiore dei Liberi’s art is preserved in the manuscripts he left behind, all entitled il Fior di Battaglia (the Flower of Battle). We know that he presented his book to the Marquise d’Este in 1409, and that at least five copies once existed. Four of these have been rediscovered, each with slight differences.

The surviving manuscripts are named for the collections that hold them: the Getty (John Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles), the Morgan (Pierpoint-Morgan Library, New York City), the Pisani-Dossi (Museo Archeologico Villa Pisani Dossi, Italy), and the Paris (Bibliothèque Nationale, France).

The Getty and Morgan manuscripts consist of illustrations accompanied by short paragraphs of text, while the Pisani-Dossi replaces the paragraphs with rhyming couplets, perhaps meant as memory aids for the student. The Getty manuscript is the largest and most detailed of the surviving texts, presenting a carefully organized learning scheme. In the prologue, Fiore provides his biography and credentials, including his five duels with other masters and the names and ranks of his most famous students and their martial accomplishments. He then presents basic tactical advice, followed by the requirements for fighting in hand-to-hand combat. The prologue ends with an explanation of the manuscript’s organization, and a dedication to Niccolo d’Este, Marquise of Ferrara.

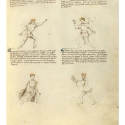

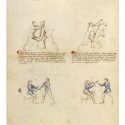

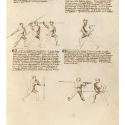

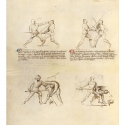

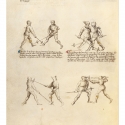

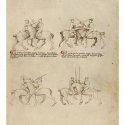

The system laid out in the Fior di Battaglia divides l’arte dell’armizare into three sections: close quarter combat, long weapon combat, and mounted combat. Within these sections, Fiore teaches his art through a series of zoghi (plays) – formal, two-person drills teaching sequences of attack and defense, similar to the two-person kata of traditional Japanese martial arts.

The close quarter combat forms the basis for many of the grappling and disarming techniques described in later sections of the manuscript, and is used in or out of armour. The dagger section contains the manuscript’s largest collection of techniques:

- Abrazare (striking, throwing, and grappling techniques)

- Bastoncello (a short stick, approximately a foot long)

- Daga (the rondel dagger)

- Daga contra spada (dagger vs. sword)

- Spada contra daga (sword vs. dagger)

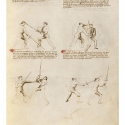

Long weapon combat begins with the introduction of the sword; swordplay forms the basis for all other long weapon combat. The treatise also includes several other knightly weapons used on foot, both in and out of armour, such as the spear and poleax. There are also several unusual weapons: specialized swords for judicial combat, and hollow-headed polehammers, meant to be filled with an acidic powder to blind the opponent! This long weapon section covers the following:

- Abrazare

- Lanza (lance)

- Spada d’un mano contra lanza (single-handed sword vs. lance)

- Spada contra spada (sword vs. sword)

- Ghiavarina (a type of bladed polearm, shown on foot against mounted opponents)

Finally, the mounted combat section reintroduces many of the disciplines already presented, this time adapted for combat on horseback, again in or out of armour. While the Guild does not practice mounted combat, advanced students study the theory of the mounted techniques, which contain many interesting insights into the other sections.

Vadi’s manuscript

Filippo Vadi’s work, De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi (On the Art of Swordsmanship), written around 1482, is very similar to the Pisani-Dossi manuscript, consisting primarily of beautifully painted figures with rhyming couplets. Vadi covers a smaller subset of weapons compared to Fiore: the dagger, the two-handed sword in and out of armour, the spear and poleaxe. The armoured combat techniques are reduced in scope. Abrazare, one-handed sword, and mounted combat techniques are omitted entirely. But De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi’s unique virtue is its prologue of sixteen verse chapters, in which Vadi addresses the general and specific principles of swordmanship: as the proper length of the sword; tactical advice for facing stronger opponents and multiple opponents; how and when to parry and to control the fight when the swords are crossed; and lessons on timing, feints, and a few specialized blows. These chapters provide fascinating insights into the tactical application of the art, and add clarity and subtlety to many of the plays found in Fiore’s manuscripts.

The above material is used with permission from Greg Mele and the Chicago Swordplay Guild.

Modern training, informed by history

The RMSG teaches Fiore’s martial art through the drills and plays Fiore himself described, adding modern pedagogy and safety precautions, historical context, and physical conditioning. It is important to understand that we are studying a martial art, not a sport; sparring against an opponent in this context is only a simulation of combat, not combat itself. Students are encouraged to view fencing not as the culmination of their training, but as another tool for developing their skills.

Solo drills are used to teach the fundamental skills of swordsmanship: balance, biomechanics, footwork, cutting, and thrusting. These drills instill in the student the ABCs of historical swordsmanship. Students rapidly progress to Fiore’s two-person drills, which contain valuable tactical lessons of time, distance, line, and control of the opponent in addition to teaching specific techniques for attack and defense. At the same time, students begin to learn free-play (sparring) via increasing the amount of randomness in the two-person drills to add the need for decision-making.

RMSG includes basic conditioning work in every class to build the flexibility, functional strength, and endurance that will help students become better fencers. This includes calisthenics and training games to reinforce correct body mechanics and skills. Successful Guild members include many who started out very unfit, as well as those with a more athletic background.

As each student becomes more skilled at competing against other fencers, they also build the intangible but equally important skills of courage, courtesy, honesty, and fair play.

Additional resources

Numerous facsimiles, translations, and commentaries of Fiore’s manuscripts are available. The most comprehensive recent work for those seeking an entry point to the study of Armizare is Volume 1 of Flowers of Battle: The Complete Martial Works of Fiore dei Liberi, by Greg Mele and Tom Leoni. This volume provides detailed historical context, a facsimile of the Getty manuscript, a translation, and play-by-play interpretation and guidance which will be appreciated by both the new student and the serious scholar.

Another excellent resource for the new student is Fiore dei Liberi’s Armizare, by Robert Charette. This is a careful visual guide to practicing the techniques, illustrated with photos from multiple angles; note however that the RMSG has some differing interpretations of several plays.